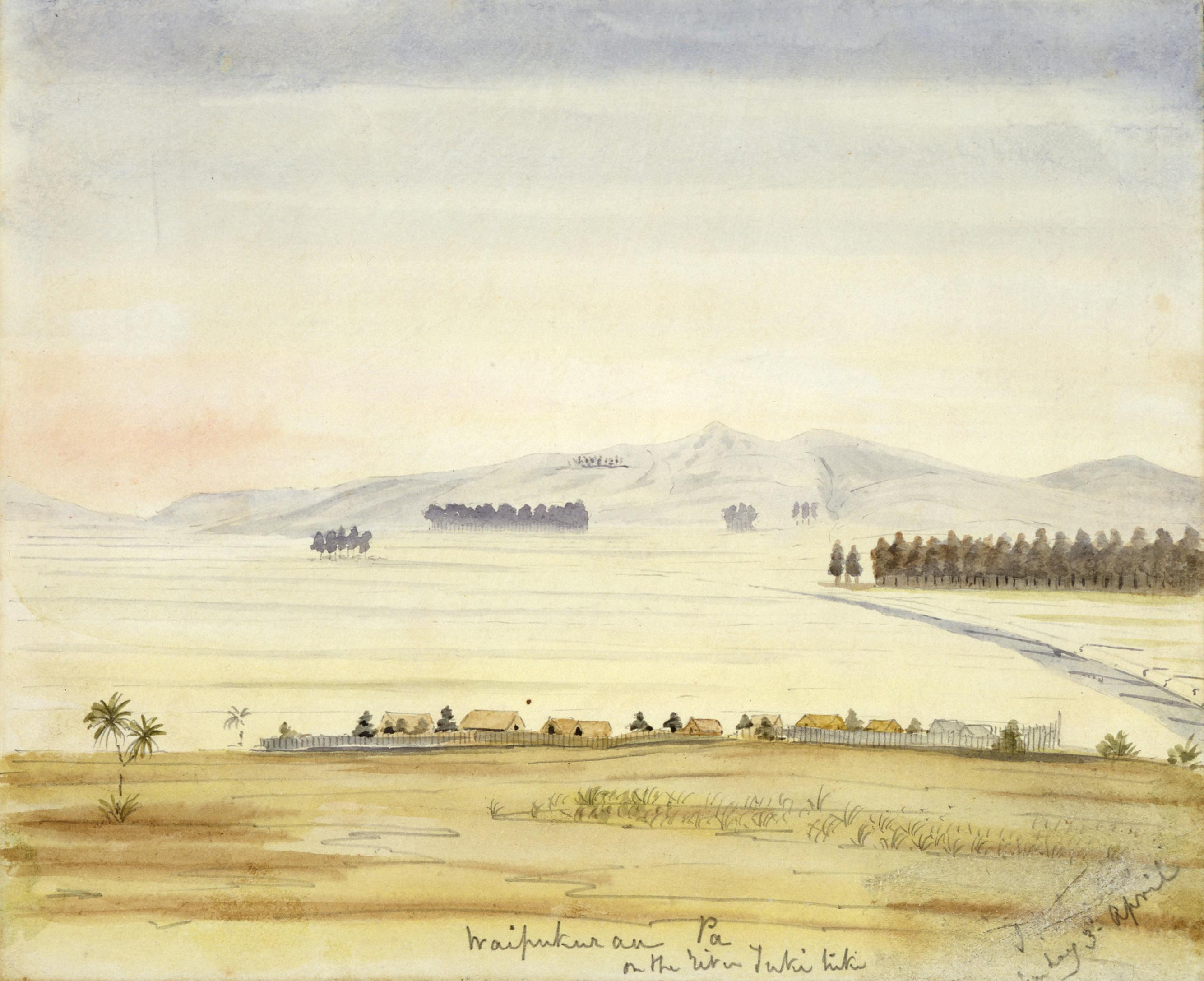

Te Waipukurau Pā

With Brian Morris & Roger Maaka

During this period, Te Waipukurau Pā became the main pā of this area. Previously, it had been a mahinga kai (food gathering place), but the returning people established it as a more permanent settlement. When missionaries came here it was Te Waipukurau Pā they visited. Māori from across the district gathered at this pā for news and trade.